Story of the National Line

A Short History of the Nigerian National Shipping Line (NNSL)

By Dr. Edmund Chilaka

The Nigerian National Shipping Line (NNSL) became one of the advanced technological companies ever to be run by an African nation-state. It was set up in 1959. Nigeria was one of only very few black African countries to venture into the trade, along with Ghana (Black Star Line), Egypt (Egyptian National Line) and Kenya (Kenya National Shipping Line). Others include Cameroon (Camships), Benin (COBENAM), Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire (SITRAM), and Congo (Compagnie Maritime Congolaise), set up as a non-vessel owning common carrier (NVOCC) mainly to manage national shipping services for the purpose of deriving invisible earnings without ship ownership and operation.

The formation of NNSL was negotiated through the local and international politics of decolonization which prevailed in the late 1950s. Subsequently, the role and utility of the company in the life of Nigerians and for the prestige of Nigeria cannot be lightly quantified. It proved to be a significant development, in fact, one of the most significant institutions for the maritime trade of West Africa, for the better part of four decades, until its liquidation in 1995. This is because NNSL was as much an investment as a protest against the monopoly and unfair practices of the mainly European carriers which dominated the shipping trade of West Africa. The colonial Governor-General at the time of its formation, Sir James Robertson, was swept along by a bandwagon he could do little about and even the champions of the Conference Lines such as Elder Dempster, Palm Line and Woermann Linie knew that politically, the game was up for colonial rule and the prevalence of imperial dictates which facilitated their dominance of the trade.

However, as will be seen in the eventual outcome of the formation and operational history of the shipping line, the maritime arena is at the heart of international politics and actual projection of power by nation states. Sometimes, sea power was exploited for economic and military gains as Great Britain did in the days when “Britania ruled the waves” in the 17th and 18th centuries. The US and Russia also exploited sea power for international politics during the cold war. Today, the EU and Asian countries are exploiting sea trade for economic predominance all over the world. Newly independent African countries, by forming shipping lines in the 1950s and 1960s, sought to claim their share of the global maritime industry in order to escape oppression, attract development and project national prestige. However, it did not quite succeed although the future still beckons if they can get their acts right and manage the largely untapped human and maritime resources in their domains which can transform them into strong maritime nations.

The Establishment of the NNSL

The story of the Nigerian national carrier, NNSL, began with movements by Nigerian politicians at both the House of Representatives and the National Economic Council (NEC) in the late 1950s. Whereas the House of Representatives comprised only Nigerians, the NEC was made up of both colonial officials and elected Nigerian politicians who served as ministers and ministerial representatives. At the NEC meeting of January 1957 chaired by the Governor-General, Robertson, eighteen ministerial representatives and ten advisers from the federal and regional governments of North, East, West and Southern Cameroon considered a memorandum tabled by the transport minister, Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, on the setting up of a national shipping company. At the House of Representatives, on the other hand, a certain legislator, Chief T.T. Solaru, voiced the desire for a national shipping line, stressing the country’s dissatisfaction with the services of the foreign carriers. Another member of the House sponsored a motion on 25th November 1958, which called for the colonial government to launch an indigenous shipping ‘enterprise’ for the country.

What type of ‘enterprise’ was the lawmaker talking about here? Without doubt, Nigerians living along the Atlantic coast or big rivers were used to transportation activities in marine environments using mainly dug-out canoes and boats of various sizes. Also, since the onset of the colonial government, the use of launches, stern wheelers, pontoons and jetties had been introduced into the inland waterway transportation systems of the country. The Government dockyards across the coastal divisions of the country were empowered to build these water crafts. Consequently, in the Niger Delta creeks, around the Lagos waters or for those communities living on the banks of rivers such as the Niger, Benue, Sokoto, Kaduna, Ogun, Numan or the Lake Chad, trading activities took place by local and foreign merchants using large canoes, wooden ships and stern wheelers. They traversed distant markets for weeks and months year in, year out. In places like the Niger Delta also, famous accounts of legendary traders and warriors who ruled maritime villages, towns and cities in Opobo, Itsekiri, Nembe, Okrika, Akassa, etc dominated pre-colonial and colonial history, including Jaja of Opobo and Nana of Itsekiri. In addition to their roles as political leaders, were also giant maritime chieftains in the 19th century.

However, the motions moved by the lawmakers in 1958 were for the establishment of the new variant of maritime trade which involved ocean trading, such as the activities of Elder Dempster, Palm Line, Hoegh Line and the other European merchants and sea traders of the colonial era. These activities were quite evident in Lagos, the Niger Delta and up the Niger and Benue as far as Lokoja, Yola, Baro and Rabbah. This new maritime trade was carried out in modern steamships which had replaced the sailing ships of the erstwhile era. By the time King Jaja traded to England carrying palm oil in the 1870s, his company was using sailing ships with all the disadvantages of poor safety, slower vessel speed and smaller economies of scale. The new maritime trade now attracting the interest of the new leaders of Nigeria was merchant marine using steamships and modern shipping management methods the way the European shipping lines were doing it. But has modern shipping been totally new and untried in Africa? How can we account for the progress of Africans in the marine navigation industry?

The name and activities of Marcus Garvey in forming the Black State Line in the USA after WWI stand out prominently in this regard. There were also the Americo-Liberian merchants of the 1830s who ran ships. According to Webster and Boahen,

Americo-Liberians were building up a substantial foreign trade by the 1830s in palm oil from the Kru coast…and their merchant ships manned by skilled Kru carried the Lone Star flag of Liberia into European and American ports. Merchant princes like R. Sherman, Joseph Roberts, Francis Devany and E.J. Roye owned ocean transports, coastal vessels and trading posts along the coast and in the hinterland.

However, such efforts by Africans have been a struggle against mountain-high obstacles in the quest to acquire or master marine technology. It is reported that in the 16th century, Affonso, the King of Kongo appealed to the King of Portugal to loan him shipwrights or “at least to sell him a ship for ocean going activities.” (Davidson 1995) One hundred years later, another African king, Kalonga Mzura, requested the same Portuguese to assist him with carpenters to build a ship for sailing on Lake Malawi and was also turned down. However, it is clear that African mastery of modern shipbuilding was not continuous or consolidated over time. Relying on statements by explorers, the continent had indigenous shipbuilding capacities by the 15th century. Davidson avers that,

[i]t was not as if Africa was lagging behind in early ship-building, for it was said that when Vasco da Gama sailed round the Cape of Good Hope in 1498, he was relieved to see at Quilimane, in Mozambique, ships that undertook frequent ocean journeys. These Mozambicans had new ships bigger than any the visitors could muster. The Portuguese even borrowed a pilot at Malinda in modern Kenya who was familiar with the route to India.

Could it be that the uncoordinated grappling with the maritime industry by present-day African leaders and the mismatch between shipping policies and national governmental actions are indicative of deep-rooted managerial deficiencies which have continued to dog the development of a virile maritime and shipbuilding industry? Has the maritime industry in Africa been hobbled by unserious political leadership and incompetent long-term planning?

However, there is wide agreement that the antecedent of forming the indigenous shipping line revolved around the longstanding perceived oppression by the foreign carriers, especially with regard to skewed freight pricing. The clamour for indigenous participation in the provision of ocean shipping was popular. Nevertheless, there was a dogged financial challenge of providing the estimated £4m project cost, not to talk of the intricate web of inter-regional politics in-country. Subsequently, the colonial government chose ocean shipping as opposed to an initial suggestion to establish a coastal service. With regard to the high project cost, the proposal by the Western Region’s delegation that West African sub-regional collaboration be explored was dropped on two grounds: the discovery that Ghana had already jumped the gun by going solo to float its own national carrier, Black Star Line, and the fact that the other regional nation-states of Sierra Leone and Gambia were not in any good financial shape to contribute to running a sub-regional shipping line.

At this juncture, it is instructive to survey the availability of skills and competency in Nigerians, or even Africans. Aside from Garvey’s attempt with Black Star Line or the Americo-Liberians who floated successful shipping lines, there was a Finnish shipping line which provided the ship operated by a collaboration between Messrs Osoba and Sons “Nigerian Line”, formed in 1957 and a certain Nordstorm & Co, from Europe. However, Osoba was widely regarded in Nigeria as a front because the ship was foreign owned and registered abroad. Even the Transport Minister, R. A. Njoku, at a point during the fractious national debates on the establishment of NNSL derided so-called ‘indigenous shipping lines’ because they set up shipping agencies in Lagos and registered them as shipping lines but were wholly owned and controlled by foreign hands.

All said, the NNSL came into being with much nationwide orchestration. It was first known as Nigerian National Line (NNL) and registered in Nigeria as a state-owned joint venture with Elder Dempster and Palm Line as technical partners. The latter were chosen out of some other bidders. There were feelings in some quarters that the company’s incorporation took place in a haste. This introduced another controversy because the Western Region felt the government took many steps in its registration without full consultation with all stakeholders in the NEC or even the House of Representatives. Perhaps the colonial government did so from hindsight, foreseeing that were aspects of the formation like the joint venture with the British lines disclosed ahead of time, it would have been scuttled by the Western and/or Eastern region governments. For example, the Western Region had suggested an alliance with Zim Lines of Israel instead of the hugely excoriated conference line champions, Elder Dempster and Palm Line Agency. The government, however, being wily and privy to certain details which were not common knowledge, like the readiness of other nations to partner with Nigeria in the enterprise, chose to patronize caution as the better side of valour.

After the act, however, the Minister rallied to build solidarity when he reported to the House of Representatives that

…on 19th December 1958, I on behalf of the Federal Government, signed an agreement with our two technical partners and this historic event has been followed by the incorporation of the Nigerian National Shipping Line Ltd. As then announced, NNSL is [a] Nigerian company with its head office in Lagos, its ships will be registered in Lagos. Nigerian interests will hold 51% of the shares and have the voting majority on the board of directors, thus ensuring complete control of the policies of the shipping line… (Wikipedia 2020)

According to Huckett (2008), training Nigerian personnel in navigation, engineering and management were crucial to the partnership agreement signed to float NNSL. Nigeria was allotted 51% of the company shares while Liverpool-based Elder Dempster held 33% and London-based Palm Line Ltd 16%. Thus, NNSL began serving the Europe-West Africa route and joined the West African Line Conference (WALCON) in May 1959. Other Nigerian lines that emerged in the following decades include Henry Stephens Shipping Ltd. which plied the Nigeria-Far East Line, Nigerian Green Lines, Nigerbrass Shipping Line and the famous Africa Ocean Line (AOL) incorporated by Chief M. K. O. Abiola with General Shehu Musa Yar’adua and Alhaji Bamanga Tukur. AOL was launched with three fully owned ships and created tremendous buzz in the land.

However, NNSL was the darling of the nation because this was the state-owned shipping line which embodied the hopes and aspirations of the new nation in the world of international merchant marine. The federal government adduced several object clauses for the formation of the company, including to project the good image of Nigeria abroad by flying the nation’s flag on the high seas and world seaports and to promote the acquisition of shipping technology by creating and diversifying employment opportunities in the shipping industry; to improve the country’s balance of payments position by enhancing the earnings and conservation of foreign exchange; to assist in the economic integration of the West and Central African sub-region; and, to support the Nigerian Navy in the event of conflict. As has been aptly noted by one commentator, “profit motive, though implied, was not the motivating factor for the company’s establishment.” (Chidi 2011)

The Structure and Operation of NNSL

The Nigerian office of NNSL was first located at 8 Labinjo Lane, in Lagos Island before moving to Development House along Wharf Road, Apapa, Lagos. A Palm Line appointee was appointed administrative manager in Lagos and at its London office at Dunster House, Mincing Lane, an Elder Dempster appointee held a similar post. However, the Liverpool office of the company was the real engine room from where ships were chartered and run. The company’s authorized share capital of £2m was raised from two million shares of £1 each divided into 400,000 founders’ shares which were allotted to Nigeria’s federal government, the Nigerian Produce Marketing Board (NPMB), Elder Dempster and Palm Line in the ratio of 104,000 shares, 100,000 shares, 132,000 shares and 64,000 shares, respectively. The NPMB at this time had taken over from European merchants the bulk purchase and export of Nigeria’s main raw materials including palm oil, palm kernel, logs, cocoa, rubber, groundnut and allied products. It naturally, as of state policy, preferred the NNSL to other carriers for lifting its products abroad and NNSL only invited other conference members to share in the carriage to the extent that it lacked the necessary shipping tonnage.

On the board of NNSL were six directors, shared equally between Nigeria and the foreign partners, but with a Nigerian, Sir Louis Ojukwu, NPMB chairman, as chairman of NNSL as well. The chairman also held the deciding vote in the case of a tie. Elder Dempster and Palm Line were also appointed as sole operational agents of NNSL in Nigeria and overseas for six years. In this role they were expected to perform certain roles, as follows: recruit managers and staff for the company and its ships; appoint ship agents and line representatives at all ports; and, provide technical advice and services to acquire ships and manage them efficiently.

The first Nigerian cadets for NNSL were trained aboard the Sulima, provided by Elder Dempster, which converted its passenger accommodation as berths for the cadets. According to Huckett, NNSL was first intended to be set up with a capital of £400,000 to be used for buying one second-hand vessel and for the charter of two others but in April 1959, Nigeria’s Finance Minister, Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh, announced a plan to increase the initial call-up capital to £1m with which to buy two ships and charter one more.

The two-year agreement NNSL signed with WALCON in 1959 stated that it (NNSL) was to operate a fleet of six ships in 1959, eight ships in 1960 and 10 ships in 1961, with a “substantial proportion” to be fully owned by the company. Beginning in May 1959, three ships were purchased that year for the NNSL’s fleet, namely, Mv Dan Fodio, Mv Oduduwa and Mv King Jaja. These were all second-hand tonnage. In 1960, two additional second-hand ships, Mv El Kanemi and Mv Oranyan were added to the fleet. In 1961, Nigeria bought all the shares of NNSL from the technical partners to take total control of the company but it retained the technical partnership of Elder Dempster and Palm Line for profitability reasons and to ensure ongoing learning curve for the Nigerian management.

NNSL’s first new building was purchased in 1962 named Mv Nnamdi Azikiwe, built by Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. The same shipyard also built another ship, Mv Ahmadu Bello, for the company in 1963. The management of the vessels was divided between the two technical partners. From the mid-1960s, more ships were acquired for NNSL including, Mv Herbert Macaulay and Mv Ovonranwem in 1965 and 1966. Between 1968 and 1969, four river class vessels – Mv River Niger, Mv River Benue, Mv River Ogun and Mv River Ethiope were added to the fleet. As the tide of the cargo flow began to change in the late 1960s, the next ship to be acquired, Mv River Hadejia, was a combo vessel designed to carry both containers and general goods. Mv Cross River was acquired in the early 1970s, bringing the fleet to 15 ships. But it has to be noted that in 1969, NNSL had its first casualty in the Mv Ovonranwem when she grounded at Sierra Leone and was sold the following year. (Huckett 2008)

However, although NNSL had been formed and was being run, nobody expected an immediate summersault in the total position of maritime trade for Nigeria. The foreign shipping lines which had exerted dominance in the country were still in control. These were Elder Dempster Line Limited, Palm Line Limited, Guinea Gulf Line, Woerman Line of Hamburg (German), Holland West Africa Line (Dutch), Barber West Africa Line (American), Farrel Lines (American), Scandinavian West Africa Line (Norwegian), Hoegh Lines (Norwegian), “K” Lines and Mitsui Osk Line (both of Japan) and Lloyds Triestino (Italian).

Table 1: Nigeria’s overseas trading transaction by merchant shipping between 1982 – 1989

| Year | Nigerian Sea-borne Trade | NNSL Carriage | % |

| 1982 | 22,611,229 | 1,420,913 | 6.3 |

| 1983 | 18,741,209 | 753, 936 | 4 |

| 1984 | 14,651,102 | 827, 546 | 5.6 |

| 1985 | 16,401,679 | 971,407 | 5.9 |

| 1986 | 12,274,579 | 699,997 | 5.7 |

| 1987 | 11,537,590 | 523, 701 | 4.5 |

| 1988 | 11,283,690 | 765,759 | 6.8 |

| 1989 | 7,513,369 | 643, 965 | 8.6 |

Source: Oyesanwo S. 1991 pg 7.

Source: Nigerian Ports Authority Handbook 1979, p.66

(See the Appendix for data on cargo volumes carried, a list of operators in the market and nationalities of ships which called at Nigerian ports.)

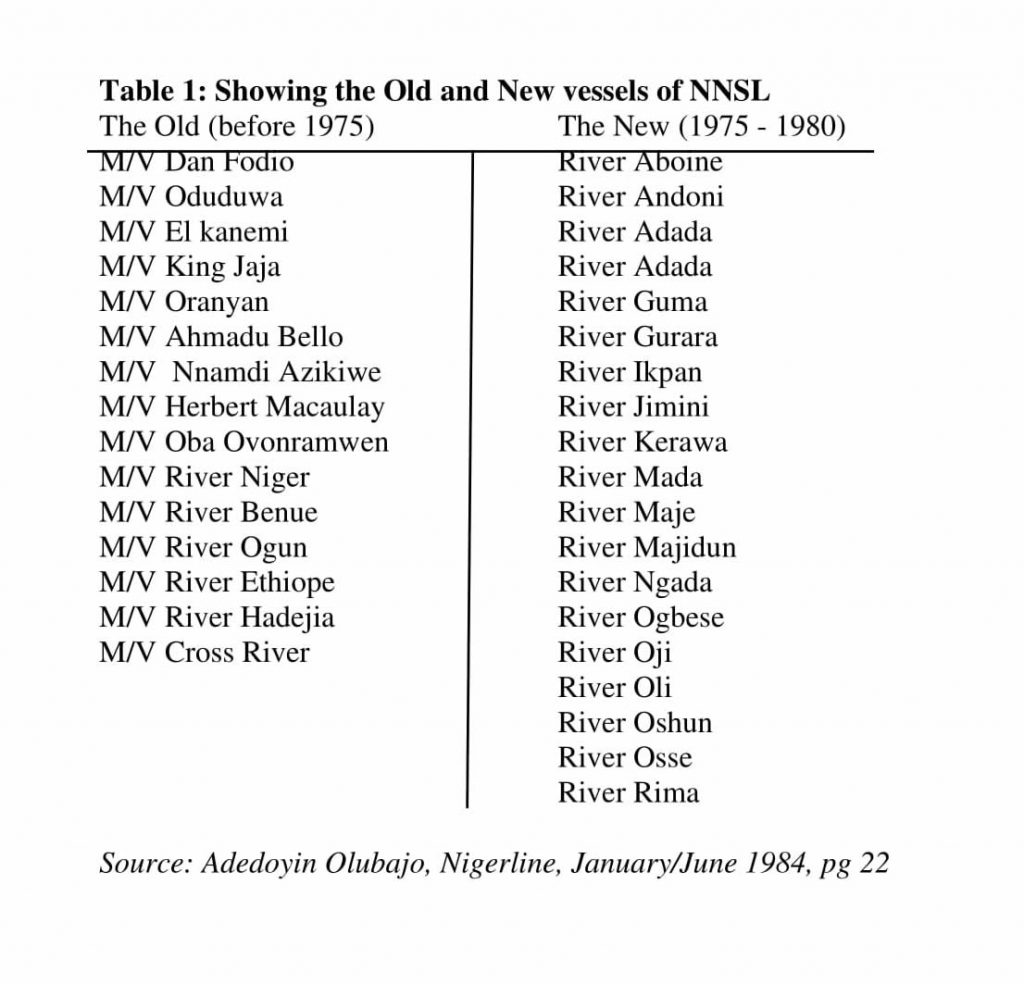

The Order of 19 New Ships

Much has been said about NNSL’s remarkable fleet increase by 19 new ships acquired in one fell swoop. The process began soon after the end of the civil war around 1972 and was included in the Third National Development Plan, 1975-1980. Subsequently, the Federal Government shelled out N176m to commission the building of 19 brand new all-purpose combo ships of fairly similar characteristics for the use of the NNSL. They were ordered from Split Shipyard of Yugoslavia and Hyundai Heavy Industries Limited of South Korea. While the former constructed eight vessels of 16,000 deadweight tons, the latter was awarded contract for the supply of eleven ships, nine of them, 12,000 deadweight tons and two weighing 16,000 deadweight tons. By 1980 when all the ships were delivered, NNSL had a fleet size of 27 ships, the largest in Africa outside of the apartheid enclave of South Africa. However, this fleet size did not remain unchanged for long. Some of the older tonnage was sold due to age and high maintenance costs. By 1989, the fleet size had reduced to a manageable 14 ships, with a total value of 208,000 deadweight tons.

Table 1: Showing the Old and New vessels of NNSL

As of 1989, NNSL belonged to six conference lines, namely: UK/West Africa Line (UKWAL); Continent/West Africa Line (COWAC); Far East/West Africa Line (FEWAC); Brazil/West Africa Line (BEWAC); Mediterranean/West Africa Line (MEWAC); and America/West Africa Line (AMWAC).

The management structure was made up of a board of directors and a committee of top management officials. The board was appointed by the Federal Government and concerned itself with broad economic, financial, operational and administrative policy guidelines and targets set sometimes by the responsible minister. For most of its lifespan, NNSL was supervised by the Federal Ministry of Transport and Aviation which was later split into two ministries. The committee of top management officials was responsible for day-to-day management of the human, financial and other resources of the company. The board is headed by the chairman, also appointed by the government while the committee of top management is headed by the managing director who is the chief executive officer.

The major departments in the company headed by directors were managing director’s office, administration, finance, operations and technical. Other divisions were public affairs, research and planning, audit, and company secretary/legal adviser. While the departments were headed by directors, the divisions were headed by assistant directors. Then there were the overseas offices manned by appointed Nigerians. While some of the departments and divisions were single compartments, others were further sub-divided for effectiveness and specialization. For example, the finance department was made up of budgeting and accounting divisions while the operations department, which was responsible for commercial running of the ships, was further sub-divided into three divisions, namely: commercial, ocean traffic control and agency. Some of the major highlights of the company’s operation, including the sinking of Mv River Gurara have been presented in other pages of this website.

Source: Nigerline, Vol.19 No.1, January- March 1989.

LIQUIDATION OF NNSL

The decision of the Federal Government to liquidate NNSL was announced by late Major General Ibrahim Gumel, then Minister of Transport, at a forum in Lagos in 1995. He said the step was taken to save Nigerian the stigma from NNSL’s operations, so that Nigerian ships would not be seized when they sailed into the waters of creditors’ nations. He assured the shipping community that the government would float another shipping company [Nigeria Unity Line] which would be handled by the National Maritime Authority. According to Gumel, the shares of the new company would be sold to interested Nigerians, ostensibly to guide against its collapse, since shareholders would thereby have a sense of belonging to monitor closely the activities of the shipping company. The role of NMA in the setup, according to him, would be that of a midwife who only assists in the delivery of the baby.

From the ministerial announcement, the liquidation of the NNSL was premised mainly on the huge debts it owed to many creditors locally and overseas. But this emphasis downplayed the enormity of other problems which confronted the company, including ageing tonnage, high maintenance costs, absence of cargo support, governmental interference, managerial ineptitude, and debts owed by Federal Government agencies. All these combined to dim the prospects of NNSL. The liquidation was considered by some observers as not having a human face because the entire workforce of NNSL was sacked without consideration for redeployment of those who still possessed capacity, experience, and youthfulness to be of service to other agencies of government – a situation that resulted in colossal waste of human resources that could have been gainfully absorbed in the national economy.

An unabridged version of the NNSL story is available online at this link, https://www.grin.com/document/508885

Bibliography

Ahutu, I. A. R., “Demise of Nigerian National Shipping Line: Implications for the National Economy”, unpublished work in the possession of the author.

Davidson, B., Africa in History quoted in Kingsley E. Usoh, The Politics of Shipping and the Nigerian Economy, Lagos: Tollbrook Publishers, 2008, 319.

Fieldhouse, D.K., Black Africa 1945-1980, Economic Decolonization & Arrested Development, London: Unwin Hyman Ltd, 1986.

Huckett, A., “Nigerian National Shipping Line, Part 1” in Ships in Focus Record 41, London: Ships in Focus Publications, 2008, 20-29.

Nigerline, ISSN:0331-4499, Vol.19, No.1, January-March 1989

“Nigerian National Shipping Line”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigerian_National_Shipping_Line accessed 23 September 2020.

Olukoju, A., “A ‘Truly Nigerian Project?’ The Politics of the Establishment of the Nigerian National Shipping Line (NNSL), 1957-1959”, International Journal of Maritime History Vol. XV No. 1, June 2003, 69-90.

Webster J.B. and Boahen, A.A., The Growth of African Civilisation, The Revolutionary Years: West Africa since 1800, London: Longmans Group Ltd, 1967, 158-159.